When Not to Automate: The Work That Still Needs a Real Owner

The Real Operational Friction

Most operational friction doesn’t show up as a single big failure. It shows up as small, repeated breaks that everyone works around. The form gets submitted, but no one answers. The customer replies, but the thread goes quiet. A refund request lands in a shared inbox, but it’s handled differently each time. Someone “took care of it,” yet the client calls again because nothing actually moved.

From the outside, it looks like the team is busy. Inside, it feels like you’re running a business made of exceptions. Every week includes a few “How did that happen?” moments: wrong addresses, duplicate records, stale quotes, missed follow-up, incomplete handoffs, approvals that stall because the approver wasn’t tagged, and reports that don’t match what people remember doing.

The cost isn’t only the rework. It’s the constant attention tax on leadership. You’re forced into triage: checking, nudging, clarifying, and re-deciding. The business doesn’t feel out of control, but it doesn’t feel stable either—and it’s hard to name why.

Why the Common Approach Fails

When things feel messy, the common instinct is to automate the annoying parts. If that doesn’t work, you hire someone “to stay on top of it.” If that still doesn’t work, you add more software, more alerts, more templates, and more rules. The result often looks more sophisticated, but it behaves the same: work still slips, and leadership still carries the burden.

Hiring more people can reduce load, but it doesn’t fix inconsistency. Two coordinators will interpret the same situation differently. A new hire will inherit partial context. Someone covers for someone else and decisions get made with different standards. Over time, you get drift: the process you intended slowly becomes a set of personal habits. The business is now dependent on who is on shift, who is in a good mood, and who remembers the “right way.”

Adding tools usually multiplies ownership ambiguity. A field gets added to track status, but who updates it? A dashboard is built, but what counts as “complete”? A ticketing lane is created, but who decides what gets escalated? Without operational ownership, tools become mirrors of confusion. They record activity, not responsibility.

Layering automations can make things worse when the underlying role isn’t clear. Automations fire when conditions are met, not when judgment is required. If the conditions are imperfect, the automation creates new work: exceptions, reversals, apologies, and manual clean-up. And when something breaks, no one is accountable because “the system did it.” That’s the quiet failure mode: lots of movement, no accountability.

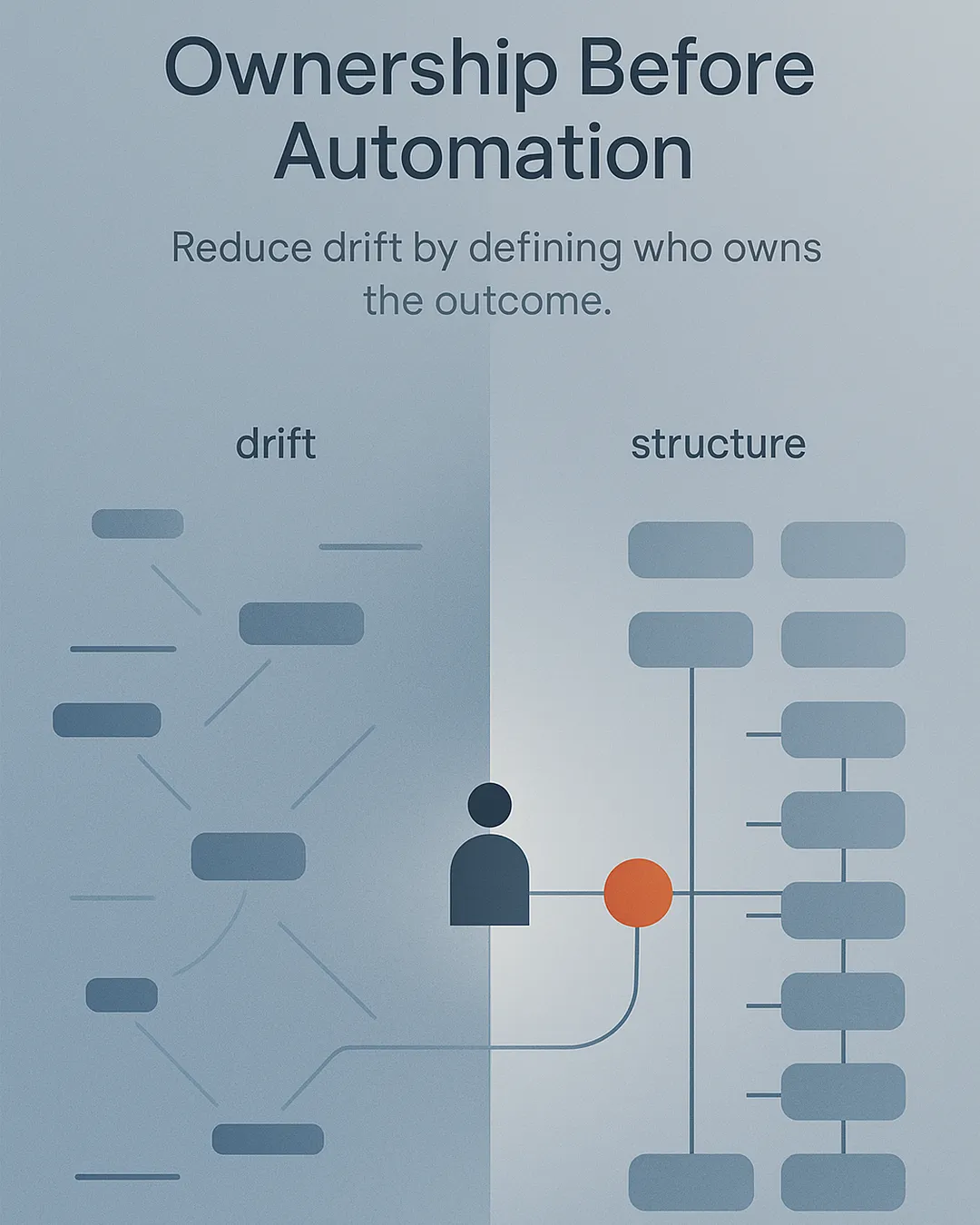

The pattern is consistent: inconsistency increases, drift accelerates, ownership becomes unclear, and accountability disappears into the gaps between people, tools, and automations.

Reframe: Roles vs Tasks

A useful way to see this is to separate tasks from roles. Tasks are the visible actions: send the follow-up, update the record, route the request, schedule the call, confirm the details. Roles are the invisible structure that makes tasks reliable: defined responsibilities, operational ownership, and an escalation path when reality doesn’t match the checklist.

Automation often fails when you try to automate tasks that actually belong to a role. For example, “send an email after a form submission” is a task. But “own intake quality” is a role. Intake quality includes checking completeness, correcting obvious errors, confirming intent, handling edge cases, and making sure the next team receives a clean handoff. If you automate the email but no one owns the role, the business still bleeds through exceptions.

So when not to automate?

Do not automate work that requires judgment without first establishing operational ownership. If the business outcome depends on context, prioritization, or a decision that changes based on customer type, risk level, or timing, then the task is not the unit to automate. The role is.

Do not automate work that is not defined. If the team can’t agree on what “done” means, automation will harden disagreement into inconsistent behavior. You’ll end up with clean-looking activity that doesn’t match expectations.

Do not automate work that has no escalation. If a process can fail silently, it will. Any repeatable function needs a clear “what happens when…” path: when data is missing, when the customer replies late, when inventory is out, when payment fails, when a VIP asks for an exception. Without escalation rules, automation just moves the failure downstream.

This is where AI employees enter as a concept: not as a layer of scripts, but as a way to treat certain functions as owned roles with defined responsibilities. The point is not to automate everything. The point is replacing repeatable roles where the boundaries are clear, ownership is explicit, and escalation is designed.

Practical Implications

When a role is owned, several things improve immediately—even before any changes to headcount or software.

First, consistency rises. The same inputs get the same handling. Edge cases are recognized, categorized, and either resolved or escalated in a standard way. You stop relying on tribal knowledge and memory.

Second, drift slows down. Defined responsibilities create a stable center: someone (or something acting as the role) is responsible for the outcome, not just the activity. If the business changes—new offer, new pricing, new service area—the role definition is what gets updated, not a scattered set of personal habits.

Third, handoffs stop breaking as often. Most operational pain lives in transitions: lead to appointment, appointment to quote, quote to invoice, invoice to fulfillment, fulfillment to support. With operational ownership, each boundary has a clear acceptance criteria. Work doesn’t move forward until it’s clean enough to move.

Fourth, leaders get time back in a specific way. You’re not just saving minutes on tasks. You’re reducing the attention tax: fewer “quick questions,” fewer rescues, fewer status pings, fewer end-of-week surprises. Your involvement becomes intentional: reviewing exceptions, improving definitions, and making real decisions—not patching gaps.

Finally, replacing repeatable roles becomes possible without increasing fragility. The business can identify which functions are stable enough to be owned by AI employees, because the role is already described in terms of outcomes, defined responsibilities, and escalation. That’s when automation stops being a gamble and starts being a controlled operational change.

Soft Close + CTA

Agentic Desk Solutions helps operators design operational ownership and defined responsibilities so replacing repeatable roles with AI employees becomes clean and accountable, not another layer of drift. If you’re considering replacing a repeatable role, we can help you map it cleanly.